Ashanti Akuaba Fertiltiy Bag

![]()

Ashanti Akua'ba Fertility Bag

The west African matrilineal Akan peoples of primarily Ghana and the Ivory Coast believe that the universe was created by a Supreme Being, whom they refer to by various names based on the spiritual forces exhibited, such as Oboadee (Creator), Nyame (God), Odomankoma (Infinite, Inventor), Ananse Kokuroko (The Great Spider; The Great Designer), etc. Wukuo which means spider, is the root for the name of the Akuaba figurines. Akua, Akúá, Akuba are female variants of this name.

A later development of the Supreme Being was Nyame (oun’-yah-may’) and Nyamewaa (oun’-yah-may’-wah), the Great God and the Great Goddess respectively, which together constitute the Supreme Being for the Akan. At the point that a fixed 7 day week calendar spread, various names were assigned to those 7 days of the week, much as the Tuetonic deities were primarily assigned to the leftover days of the week (Sun’s day, Moon’s day, Tues’ day, Wodan’s day. Thor’s day, Friya’s day and Saturn’s day) in the Roman culture. The developing religion had Nyame and Nyamewaa placing seven of their children over the seven days of the week. Wednesday was named for Ananse Kokuroko, The Great Spider, Great Designer under the female name of Akua (a-kwee-ya).

When a child is born, the Supreme Being puts part of His/Her spiritual form into human beings as the human soul (kra). This soul in the human being never perishes. The Akan believe that the soul never dies. This soul reincarnates. So when a child is born, the Akan give the child a soul name (kra din), designated by the day of the week on which the child was born. The eighth day is the day of the naming ceremony (den to). The second name of the child is the order in which the child was born to the mother.

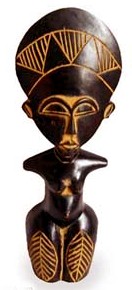

The Akua'ba statuettes are fertility figures. Ba means child in Akan. Original Akuaba’s or Akaba’s were female, primarily because Akan society is matrilineal, so women prefer female children who will perpetuate the matrilineal family line. The Akan were originally from the Sahel territory of Northern Africa. They migrated south into Guan territory and some of the Akan merged with the Guan, a patrilineal culture. A much later account from the patrilineal culture of the Guan, for the naming of these Akua’ba figures, is that of a barren woman named Akua (women are frequently barren in patriarchal stories, needing the help of the patriarchal priesthood and the male god for fertility – a major revisionist history of fertility). She was advised by the patriarchal priest to carry a wooden child to help with her infertility. Akua's first child was a girl. Women then imitated Akua, by carrying the wooden images for fertility. The older matrilineal account derives from the Great Spider, the Creatress, who carries her young on her back.

The Akua’ba symbolizes life in this world. The woman wears the Akua’ba on her back and tends to it like a child, hoping the Supreme Being will see that she will be a good mother. After influencing pregnancy, the mother gives birth to a daughter, she may give the Akua’ba to her daughter to care for (this type of gift teaches child care). Sometimes the Akua’ba are returned to shrines as offerings to the Supreme Being who responded to the appeals for a child. A collection of figures becomes an advertisement for the Supreme Being’s ability to help women conceive. Families may also keep an Akua’ba as memorials to a child or children.

The Akua’ba represents a woman’s desire for offspring. But in the matrilineal eyes, daughters are valuable, not something that is worthless, to be killed when born, as occurs even today or property for trading. These women not only wanted and prayed for a daughter, they put their faith into action, visualizing their hope. I would be curious as to the ratio of daughters born to these ancient mothers who so desired their daughters that they carved them in wood and carried them on their backs, tending to them before they were even conceived.

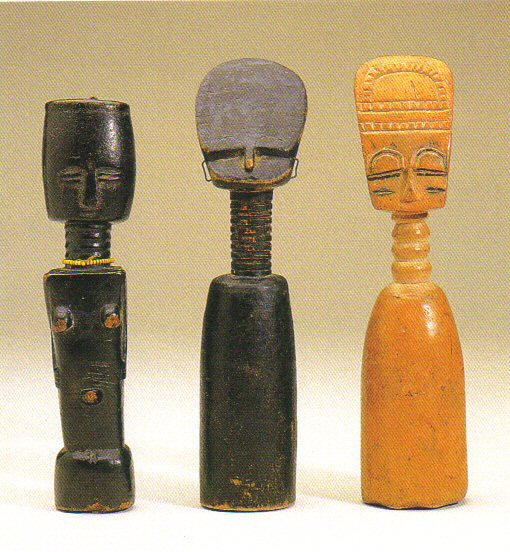

The best known Akua’ba are from the Ashanti (Asante) tribe in Ghana with round disk heads. While most Ashanti figures are painted black, the Fante tribe figures are left unpainted. The Brong tribe, living to the west of the Ashanti, carve Akua'ba with cylindrical heads cut diagonally from the top back to the bottom front, producing a triangle in profile. Generally the undecorated cylindrical torso is rounded on top and limbless. Many older Akua'ba do not have naturalistic arms and legs. Often the Akua’ba are decorated with designs common to the family or tribe, or carrying nature elements that were important to the matrilineal culture.